Cash Flow

This week on MBA Mondays we are going to talk about cash flow. A few weeks ago, in my post on Accounting, I said there were three major accounting statements. We’ve talked about the Income Statement and the Balance Sheet. The third is the Cash Flow Statement.

I’ve never been that interested in the Cash Flow Statement per se. The standard form of a cash flow statement is a bit hard to comprehend in my opinion and I don’t think it does a very good job of describing the various aspects of cash flow in a business.

That said, let’s start with the concept of cash flow and we’ll come back to the accounting treatment.

Cash flow is the amount of cash your business either produces or consumes in a given period, typically a month, quarter, or year. You might think that is the same as the profit of the business, but that is not correct for a bunch of reasons.

The profit of a business is the difference between revenues and expenses. If revenues are greater than expenses, your business is producing a profit. If expenses are greater than revenues, your business is producing a loss.

But there are many examples of profitable businesses that consume cash. And there are also examples of unprofitable businesses that produce cash, at least for a period of time.

Here’s why.

As I explained in the Income Statement post, revenues are recognized as they are earned, not necessarily when they are collected. And expenses are recognized as they are incurred, not necessarily when they are paid for. Also, some things you might think of as expenses of a business, like buying servers, are actually posted to the Balance Sheet as property of the business and then depreciated (ie expensed) over time.

So if you have a business with significant hardware requirements, like a hosting business for example, you might be generating a profit on paper but the cash outlays you are making to buy servers may mean your business is cash flow negative.

Another example in the opposite direction would be a software as a service business where your company gets paid a year in advance for your software subscription revenues. You collect the revenue upfront but recognize it over the course of the year. So in the month you collect the revenue from a big customer, you might be cash flow positive, but your Income Statement would show the business operating at a loss.

Cash flow is really easy to calculate. It’s the difference between your cash balance at the start of whatever period you are measuring and the end of that period. Let’s say you start the year with $1mm in cash and end the year with $2mm in cash. Your cash flow for the year is positive by $1mm. If you start the year with $1mm in cash and end the year with no cash, your cash flow for the year is negative by $1mm.

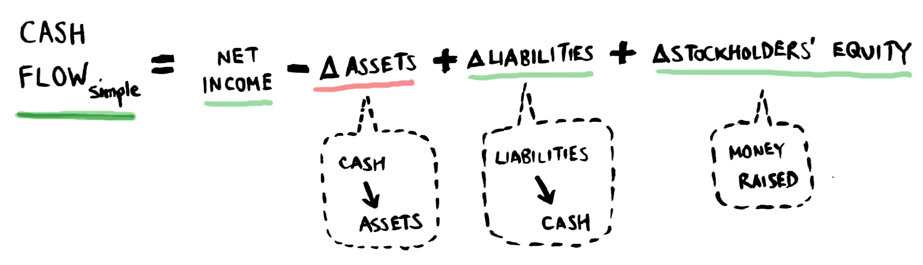

But as you might imagine the accounting version of the cash flow statement is not that simple. Instead of getting into the standard form, which as I said I don’t really like, let’s talk about a simpler form that gets you to mostly the same place.

Let’s say you want to do a cash flow statement for the past year. You start with your Net Income number from your Income Statement for the year. Let’s say that number is $1mm of positive net income.

Then you look at your Balance Sheet from the prior year and the current year. Look at the Current Assets (less cash) at the start of the year and the Current Assets (less cash) at the end of the year. If they have gone up, let’s say by $500,000, then you subtract that number from your Net Income. The reason you subtract the number is your business used some of your cash to increase its current assets. One typical reason for that is your Accounts Receivable went up because your customers are taking longer to pay you.

Then look at your Non-Current Assets at the start of the year and the end of the year. If they have gone up, let’s say by $500k, then you also subtract that number from your Net Income. The reason is your business used some of your cash to increase its Non-Current Assets, most likely Property, Plant, and Equipment (like servers).

At this point, halfway through this simplified cash flow statement, your business that had a Net Income of $1mm produced no cash because $500k of it went to current assets and $500k of it went to non-current assets.

Liabilities work the other way. If they go up, you add the number to Net Income. Let’s start with Current Liabilities such as Accounts Payable (money you owe your suppliers, etc). If that number goes up by $250k over the course of the year, you are effectively using your suppliers to finance your business. Another reason current liabilities could go up is Deferred Revenue went up. That would mean you are effectively using your customers to finance your business (like that software as a service example earlier on in this post).

Then look at Long Term Liabilities. Let’s say they went up by $500k because you borrowed $500k from the bank to purchase the servers that caused your Non-Current Assets to go up by $500k. So add that $500k to Net Income as well.

Now, the simplified cash flow statement is showing $750k of positive cash flow. But we have one more section of the Balance Sheet to deal with, Stockholders Equity. For Stockholders Equity, you need to back out the current year’s net income because we started with that. Once you do that, the main reason Stockholders Equity would go up would be an equity raise. Let’s say you raised $1mm of venture capital during the year and so Stockholder’s Equity went up by $1mm. You’d add that $1mm to Net Income as well.

So, that’s basically it. You start with $1mm of Net Income, subtract $500k of increased current assets, subtract $500k of increased non-current assets, add $250k of increased current liabilities, add $500k of increased long-term liabilities, and add $1mm of increased stockholders equity, and you get positive cash flow of $1.75mm.

Of course, you’ll want to check this against the cash balance at the start of the year and the end of the year to make sure that in fact cash did go up by $1.75mm. If it didn’t, then you have to go back and check your math.

So why would anyone want to do the cash flow statement the long way if you can simply compare cash at the start of the year and the end of the year? The answer is that doing a full-blown cash flow statement tells you a lot about where you are consuming or producing cash. And you can use that information to do something about it.

Let’s say that your cash flow is weak because your accounts receivable are way too high. You can hire a dedicated collections person. You can start cutting off customers who are paying you too late. Or you can do a combination of both. Bringing down accounts receivable is a great way to improve a business’ cash flow.

Let’s say you are spending a boatload on hardware to ramp up your web service’s capacity. And it is bringing your cash flow down. If you are profitable or have good financial backers, you can go to a bank and borrow against those servers. You can match non-current assets to long-term liabilities so that together they don’t impact the cash flow of your business.

Let’s say your current liabilities went down over the past year by $500k. That’s a $500k reduction in your cash flow. Maybe you are paying your bills much more quickly than you did when you started the business and had no cash. You might instruct your accounting team to slow down bill payment a bit and bring it back in line with prior practices. That could help produce better cash flow.

These are but a few examples of the kinds of things you can learn by doing a cash flow statement. It’s simply not enough to look at the Income Statement and the Balance Sheet. You need to understand the third piece of the puzzle to see the business in its entirety.

One last point and I am done with this week’s post. When you are doing projections for future years, I encourage management teams to project the income statement first, then the cash flow statement, and then end up with the balance sheet. You can make assumptions about how the line items in the Income Statement will cause the various Balance Sheet items to change (like Accounts Receivable should be equal to the past three months of revenue) and then lay all that out as a cash flow statement and then take the changes in the various items in the cash flow statement to build the Balance Sheet. I like to do that in monthly form. We’ll talk more about projections next week because I think this is a very important subject for startups and entrepreneurial management teams to wrap their heads around.

From the comments

Philip Sugar offered:

I have a spreadsheet that I’ve developed over the last fifteen years that ties all three together.

I’m willing to open source it.

Important to note the one thing you can’t fudge is cash. Everything else accountants can manipulate.

…

Here you go: https://spreadsheets.google.co…

JLM added:

The cash flow statement is very easy to derive and understand if you will remember some very, very simple rules. Before you start, get out your income statement and your balance sheet and your cash receipts/disbursements journals and review the results.

If you use QuikBooks to handle your accounting all this stuff is automatically available at a push of a button once you have entered everything.

Income statement is operating performance over time and balance sheet is a snapshot which can be compared to the same starting period as the income statement thereby signalling changes over the same time period.

The cash flow statement is derived from three (3) simple questions or areas of emphasis:

1. What were the results of “operations”? Did we generate or consume cash through operations? <<< look at the income statement to answer this question

1A. What non-cash costs were included in “operations” which should be backed out? Depreciation? Amortization? Stock based compensation? Gain or sale of a business unit which was included in opertions? Asset impairments and contract termination costs. <<< look at the income statement for non-cash expenses

1B. What happened to our asset and liability account balances? Did accounts receivable go up or down? What happened to our trade accounts payable? How about accrued expenses and other current liabilities? <<< look at the balance sheet

2. What was the impact of “investing activities”? Did we purchase any property, plant or equipment? Did we purchase any goodwill or intangibles? Did we sell sell any equipment? Did we receive repayment of any promissory notes? <<< look at the balance sheet and your cash disbursements/receipts journal

3. What was the impact of “financing activities”? Did we borrow any money? Pay off any debt? Receive any settlements? Sell any common stock? Repurchase any common stock? Receive any proceeds from the exercise of options? <<< look at the balance sheet and cash receipts/disbursements journal

In it simplest form the cash flow statement starts with the cash/cash equivalents at the BEGINNING of the term and then adds/subtracts the results of —

Operations

Investing activities

Financing activitiesresulting in the cash/cash equivalents on hand at the END of the period.

Remember the convention on the +/- sign will always be — did this item generate (+) or consume (-) cash?

Check, double check and re-check the ending cash balance with your bank balances to ensure they match. Whatever your cash flow statement says is the ending cash amount must be somewhere — like in your bank accounts.

The first couple times can be a bit confusing but it all makes sense if you ask yourself whether something generated or consumed cash and whether it is truly a cash cost or not!

Go through it w/ a CPA a couple of times and it will be perfectly clear.

This post was originally written by Fred Wilson on March 29, 2010 here.