Scenarios

In last week’s MBA Mondays, I introduced the topic that we’ll be focused on for the next month or so; projections, budgeting, and forecasting. In that post, I described projecting as a “what if” exercise that is done at a higher level of abstraction than the budgeting and forecasting exercises. I said this about projections:

These are a set of numbers, both financial and operational, that you make about your business for various purposes, including raising capital. They are aspirational and are often done with a “what could be” perspective.

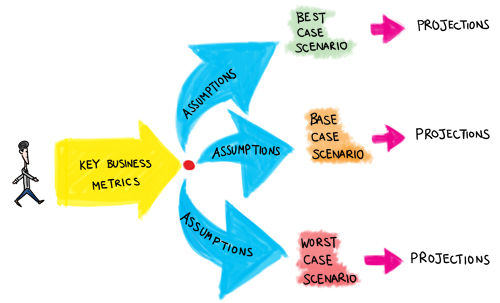

Since projections are not budgets and are much more “big picture” exercises, it is important to use a scenario driven approach to them. I generally like three scenarios; best case, base case, and worst case. But you could do as many scenarios as you like. It’s not the results that matter so much, it’s the process and the learning that comes from the projections exercise.

If you build your projections with a detailed set of assumptions and if you can assign probabilities to each assumption, you could easily do a monte carlo simulation in which literally thousands, or tens of thousands, of scenarios are run and the outcomes are charted on a bell curve. I don’t recommend doing projections this way, but my point is simply that the number of scenarios is not important, it’s the process by which you determine the key drivers of the business, the assumptions about them, and the probabilities associated with them.

A few weeks ago on MBA Mondays we talked about key business metrics. It is very important to identify your key business metrics before you do projections. These key business metrics will drive your projections and your assumptions about how these metrics will develop over time will determine how your scenarios play out.

Let’s get specific here. I’ll assume we are operating a software business and we are selling the software as a service over the internet using a freemium model. Everyone can use a lightweight version of the software for free, but to get the fully featured version the user must pay $9.95 per month. So here are some of the key business metrics you might use in projecting the business; productivity of the engineering team, feature release cycle, current outstanding known software bugs, total users, new free users per month, conversion rate from free to paid, marketing dollars invested per new free user, marketing dollars invested per new paid user; customer support incidents per day; cost to close a customer support incident. These are just examples of key business metrics you can use. Every business will have a different set.

The next step is to lay all of these metrics out in a spreadsheet and make assumptions about them. As I said, I like three assumptions, best case, base case, and worst case. Best case is not the best it could ever be but best you think it will ever be. Base case is what you genuinely expect it to be. And worst case should be the worst it could ever be. Worst case is really important. This is your nightmare scenario.

You then calculate your costs and revenues as a function of these metrics. There are some expenses that will not vary bases on the assumptions. Rent is a good example of that in the short term. But over time, rent will move up if you need to hire like crazy. I would go out at least three years in a projections exercise. Some people like to go out five years. I’ve even seen ten year projections. I don’t think any technology driven business can project out ten years. I am not even sure about five years. I believe three years is ideal.

Getting the assumptions right and building up to a full blown projected profit and loss statement is an iterative process. You will not get it right the first time. But if you build the spreadsheet correctly the iterating process is not too painful. Do not do this exercise all by yourself. It should be done by a team of people. If you are a one person company right now, then show the results to friends, advisors, potential investors. Get feedback on your key business metrics, assumptions, and results. Think about the results. Do they make sense? Are they achievable?

In last week’s comment thread we got into a conversation about “top down” vs “bottom up” analysis. Top down is when you say “the market size is $1bn, we can get 10% of it, so we’ll be a $100mm business.” I think top driven analysis is not very rigorous and likely to produce bad answers .The kind of projection work I’ve been talking about in this post is “bottom up” and is based on what can actually be achieved. However, it is often best to take the results of a bottom up analysis and do a reality check using a top down analysis.

So when your best case scenario has your business at $100mm in revenues in year three, do yourself a favor and do a top down reality check on that. No matter how rigorous the projections process is, if the results are not believable then the whole exercise will have been wasted.

Most entrepreneurs do projections as part of a financing process. And it is a good idea to have projections for your business when you go out to raise money. But I would advise entrepreneurs to do projections for themselves too. It is a good idea to have some idea of what you are building to. Make sure it is not a waste of time for you and the team your recruit to join you.

It is true that most great tech businesses, possibly all businesses, are initially built to “scratch an itch.” But once you get past the “I built this because I wanted it” and when you find yourself hiring people, raising capital, renting space, it’s time to think about what you are doing as a business and having solid projections and a few scenarios is a really good way to do that.

From the comments

JLM spoke about his experience with projections and scenarios:

The ability to predict a set of future cash flows from a set of assumptions is the essence of business forecasting and modeling. I have done this literally thousands of times and though I have the calmness of having seen the same movie a thousand times, I am still always in suspense awaiting the denouement. I always run out of popcorn before the credits run.

The only useful things I have learned are:

Document all the assumptions and make the first tough conversations not about the spreadsheet that results from applying the assumptions but the assumptions themselves thereby foregoing our general nature of rooting for a particular outcome. I tend to root for John Wayne and hey, sometimes but not too frequently, he is NOT going to get the girl.

Take a minute to write out the logic of the assumptions and the ranges you have picked. Put allthe assumptions on the first sheet of the spreadsheet so you cannot see the spreadsheet as one peruses the assumptions.

I don’t really care whether there are 3-5 different sets of assumptions and how they are mixed and matched. I just want to know why someone picks a particular set of assumptions but always BEFORE I see the finished spreadsheet. Then I become influenced by the outcome rather than the assumptions. Like seeing the end of the movie before the first scene. Nah! Not good.

Make your scenarios flow from the range of reasonable assumptions not from the finished product. The scenarios should simply dance to the assumptions and not be “bashed to fit”. There is nothing worse than “adjusting” a spreadsheet because you don’t like the outcome. Guilty!

Try to separate all fixed costs (rent, utilities, even people to a certain extent) from the variable revenues/costs thereby understanding that there is a “nut” which must be cracked regardless of what happens with the variables. How much is fixed and how much is variable? How much of the variable is directly controllable and how much is not? Try to get a handle on what percentage of the business is left to the whims of the gods. What the hell can you really manage?

Graph as many of the outcomes and variables over to time to see if the graphical image seems reasonable. I have kept myself from wandering into the swamp a few times when confronted by the slope of the curve and saying — wow, that doesn’t look right.

Get a lot of feedback from others. A lot of feedback but always start w/ the assumptions. It is great to learn from experience but it is much less expensive to learn from somebody else’s experience.

Most things take twice as long and cost twice as much as we initially think they will. Understand and anticipate this.

Continually update your forecasts as you sink your teeth into the business. I would update any forecast every 90 days even if the update was just to change the damn date. As the real numbers begin to emerge your confidence interval will close because the assumptions will now become realities.

Point of order — when making forecasts to raise money or get a deal done, don’t be afraid to apply just a smidge of vaseline because the money guys are going to arrive w/ the clipping shears in hand. As they said in the Godfather — this is the business we have chosen!

Bad fact — some deals don’t work. Don’t beat a dead horse.

This article was originally written by Fred Wilson on May 3, 2010 here.