Hedging

This is the third in a series of MBA Mondays posts about risk and return. Last week we talked about diversification, my favorite form of risk mitigation. This week we are going to talk about another favorite risk mitigation method of mine – hedging.

There are different types of investors in any highly developed and liquid market. There are speculators who are looking to make risky bets and you can use them to reduce your risk by taking the opposite side of those bets. Doing this is called hedging.

Let’s go through some real world examples. The simplest one is shorting a stock that you own. Let’s say you own 1,000 shares of Apple that you bought during the 2008 market break at $75/share. The Apple shares are now at $267/share and you are worried that the iPhone 4 reception problems are going to hurt the stock in the short term. You could sell the stock, but you really don’t want to. So you can short 1,000 shares of Apple for as long as you are nervous.

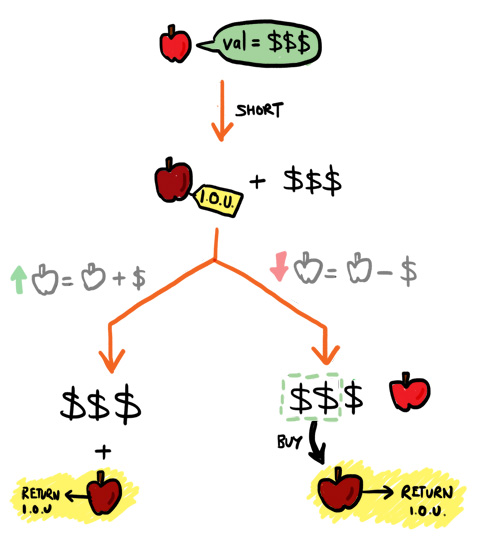

The way shorting a stock works is someone who also owns the stock loans you the shares and you sell them. You promise to give them back the stock at some future date. You pocket the $267,000 you get from selling the Apple stock but you have a liability which is you have to give the stock back to the person or institution who loaned it to you. Fortunately, you still own the stock you originally purchased so you can always pay back the loan in the stock you own. If the stock goes down, you can use some of the $267,000 you got in the sale of stock to buy back the Apple stock at a lower price and use that to repay the loan. If the stock goes up, you are losing money on your short, but making exactly the same amount on the stock you originally bought.

In this scenario, you have hedged your risk of the stock going down, but you are also not going to make any money if the stock goes up. It is like you sold the stock except that you still have your original stock in your possession. You are perfectly hedged except for counterparty risk, which are risks brought on by the other party to your hedging transaction. In this case, counterparty risk is pretty low.

Another form of hedging involves options. There are two primary forms of options, puts and calls. A put option gives you the option of “putting” your stock to someone else at a specific price. A call option gives you the option of “calling” a stock from someone else at a specific price.

Let’s continue this example of Apple stock at $267/share. Instead of shorting the stock you can use options to hedge your position. The simplest form of a hedge is to buy a put to protect your downside. Let’s say you want to make sure you get $250/share for your Apple stock no matter what. You can buy a put that allows you to “put” your Apple stock for $250/share until August 10th (a little more than 5 weeks) for $27. If that happens, you actually are getting $223/share because you’ll get $250/share but you had to pay $27 for the call. That is the purest form of downside protection. It is expensive, but you get to keep all of the upside on the stock. And there is counterparty risk because if the person selling you the put goes out of business, they won’t be there to honor the call.

If you are willing to give up some upside, then a better approach is the “collar”. In this trade you buy a put and sell a call. The August 10th Apple put at $250 is trading at $27 right now. To finance that cost, you can sell an Aug 10th Apple $280 call for $24. You are still out $3/share but it is must less expensive insurance. However, if the stock goes up to $280, it can get called from you.

I got all these option prices from the CBOE’s website. These are the current prices as of Monday morning before the markets open. These prices will move around a lot, reflecting both the price of Apple stock, the remaining time until expiration of the option, and the volatility of the stock.

If you think about the collar, it is a lot like shorting a stock you already own. You are protected if the stock goes down but you aren’t going to make much if the stock goes up.

When our venture capital firm finds itself with a lot of public stock that we cannot sell for one or more reasons and we want to protect ourself from downside risk, we like to use a collar. You can use traded options, like the ones I am quoting from the CBOE. Or you can get a trading desk at a major brokerage firm to create synthetic options for you. No matter what you do with collars, it is going to cost something. You are purchasing insurance and insurance has a cost.

It is important to remember the counterparty risk when you are hedging. No hedge is any good if the other party to the transaction is not there to settle up. It is like buying insurance. You want to buy insurance from a highly rated carrier and you want to do hedging transactions with financially secure and stable counterparties. What constitutes that these days is another issue.

In summary, when you have a large gain on your hands, think about taking some of that gain off the table by selling it and diversifying. If you can’t do that for one reason or another (taxes is a common one), think about a hedging transaction.

From the comments

Jerome Camblain chimed in with:

Correlation and systemic risk are the thing to consider when hedging.

Example: I work for a great company that is stronger than its direct competition but the overall sector is over priced, or the economy in trouble…. I can then short a basket of my competitors stocks in order to hedge against the industry valuation while keeping a relative upside on my firm.

This is Extracting the specific value (the Alpha) versus the market exposure (the Beta). Most firms or CEO use this technique on stocks they are restricted to sell.In Europe there is another mitigation technique for restricted sellers (founders); a fund is created and the promotor approaches 50+ startups founders who exchange (option contract usually) a piece of their startup against a piece of the newly created basket. Two great effects: risk mitigation and creation of a great network for creation of value and partnersips for your firm.

This article was originally written by Fred Wilson on June 28, 2010 here.